We live surrounded by objects we think we understand. The chair you're sitting on, the screen you're reading from, the coffee mug that's probably within arm's reach—they seem straightforward. But dig just beneath the surface, and you'll find layers of history, science, and human ingenuity that transform the mundane into the extraordinary.

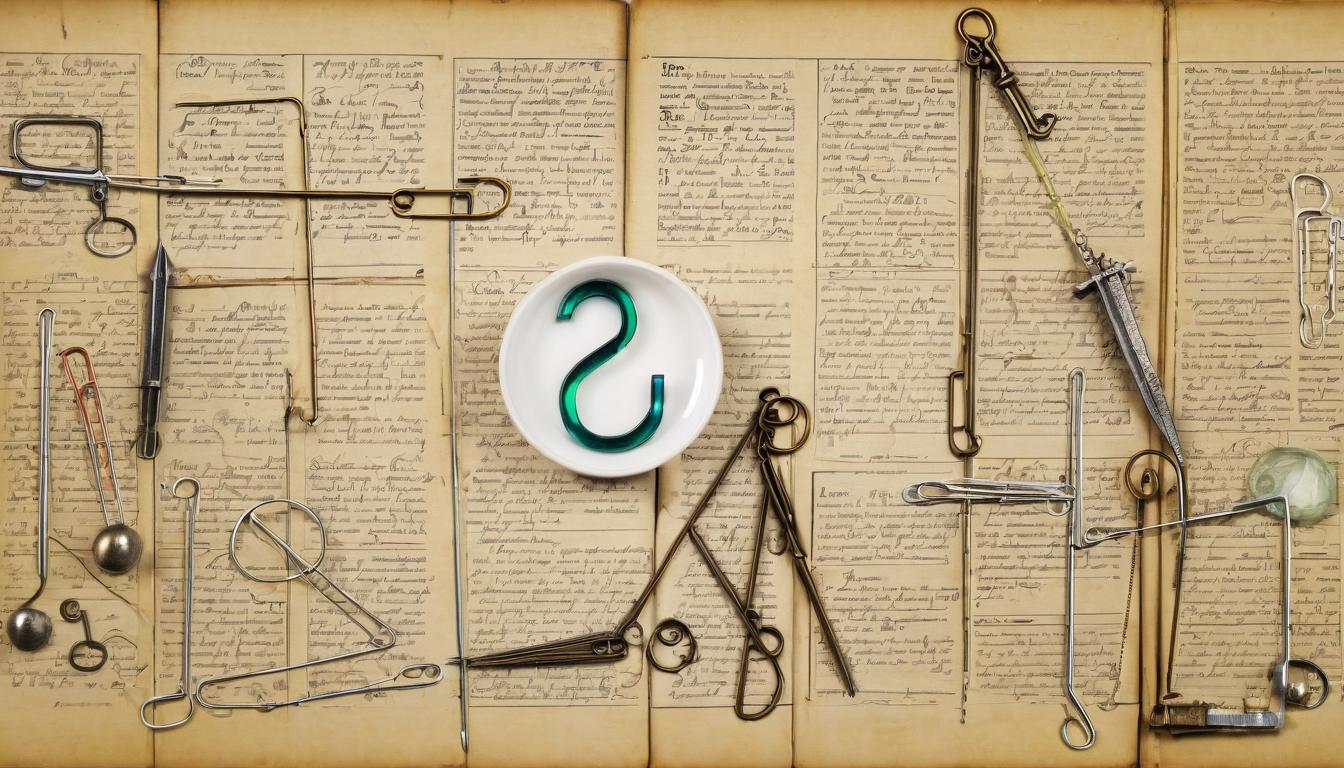

Take the humble paperclip, for instance. This simple bent wire seems about as basic as technology gets. Yet its evolution reveals a story of industrial espionage, patent wars, and accidental genius. The Gem paperclip we recognize today wasn't actually patented—its Norwegian inventors believed it was too simple to deserve legal protection. During World War II, Norwegians wore paperclips on their lapels as silent protests against Nazi occupation, turning stationery into symbols of resistance.

Then there's the zipper, which took over twenty years to become commercially viable. Its inventor, Whitcomb Judson, originally called it the "clasp locker" and debuted it at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair as a solution for people who struggled with buttoning boots. Early versions constantly jammed or sprang open unexpectedly. It wasn't until Gideon Sundback redesigned it with interlocking teeth that the modern zipper emerged—yet it still took another decade before fashion designers considered it anything but a novelty.

Our relationship with everyday materials reveals equally surprising stories. Glass, for example, is neither a solid nor a liquid in the traditional sense. It's an "amorphous solid" that flows so slowly—over centuries—that medieval cathedral windows are measurably thicker at the bottom. This isn't because artisans installed them incorrectly, but because the glass has been gradually descending under gravity since the day it was made.

Even something as simple as a pencil contains hidden complexity. The average pencil can draw a line 35 miles long or write approximately 45,000 words. That graphite core isn't actually lead—it's carbon mixed with clay, a formulation discovered when a lightning strike revealed a massive graphite deposit in England in the 16th century. The eraser on the end? That was an accidental innovation by Hyman Lipman, who patented the idea of attaching an eraser to a pencil in 1858, creating the first truly mistake-friendly writing tool.

Food packaging tells its own tales of innovation. The ring pull on soda cans was invented by Ermal Fraze in 1962 after he found himself at a picnic without a can opener. His original design—the pull-tab that completely separated from the can—created litter problems until Daniel Cudzik invented the stay-on tab in 1975. Those little bumps on the bottom of soda cans? They're not just for decoration—they're engineered to withstand up to 90 pounds of pressure, about three times what's inside a typical can.

Our digital devices harbor even more secrets. The QWERTY keyboard layout wasn't designed for speed—it was actually created to slow typists down. Early typewriters jammed when adjacent keys were pressed too quickly, so Christopher Sholes rearranged the letters to separate common combinations. The design stuck through technological evolution, creating a standard based on solving a problem that no longer exists.

Even the plastic around us has surprising origins. The first fully synthetic plastic, Bakelite, was invented in 1907 by Leo Baekeland, who was actually trying to create a synthetic substitute for shellac. His accidental discovery launched the plastic age, but few realize that many early plastics were marketed as environmentally friendly alternatives to ivory and tortoiseshell, which were driving certain species toward extinction.

The stickers on fruit? Those little codes reveal whether produce is conventional (four digits), organic (five digits starting with 9), or genetically modified (five digits starting with 8). It's a global language understood by cashiers and scanners worldwide, yet completely invisible to most shoppers.

Our buildings contain hidden engineering marvels. The dots on glass skyscrapers aren't decorative—they're ceramic frit patterns that reduce heat gain and bird collisions. The tiny gaps between sidewalk squares aren't oversights—they're expansion joints that prevent concrete from cracking as it expands and contracts with temperature changes.

Perhaps most surprisingly, many everyday objects have military origins. Microwave ovens emerged from radar technology developed during World War II, when engineer Percy Spencer noticed a candy bar melting in his pocket near active radar equipment. GPS, the technology that guides our road trips and food deliveries, was originally created for military navigation, with civilian access intentionally limited until 2000.

These stories remind us that nothing in our manufactured world is truly simple. Every object represents countless decisions, accidents, and innovations spanning generations. The next time you use a zipper or type on a keyboard, you're participating in a history far richer than the object itself suggests. The ordinary becomes extraordinary when you understand the invisible layers of human creativity that brought it into being.

The hidden lives of everyday objects and the surprising truths behind them