History is filled with strange tales that often get overlooked in textbooks, but some of the most fascinating stories involve the bizarre journeys of historical artifacts. One of the most peculiar cases involves Napoleon Bonaparte—not his military campaigns or political maneuvers, but what happened to his body parts after death. During the autopsy performed on the exiled emperor in 1821, several organs were removed, including his heart and stomach. But somehow, his penis allegedly went missing and began its own incredible journey through history.

For decades, Napoleon's purported member passed through various collectors' hands, described in auction catalogs as a 'mummified tendon.' In 1927, it was purchased by an American urologist who displayed it proudly in his New Jersey home. The artifact eventually made its way to a London auction house where it sold for thousands of dollars in the 1970s. Today, its whereabouts remain uncertain, leaving historians to debate both its authenticity and the strange fascination with collecting such macabre souvenirs.

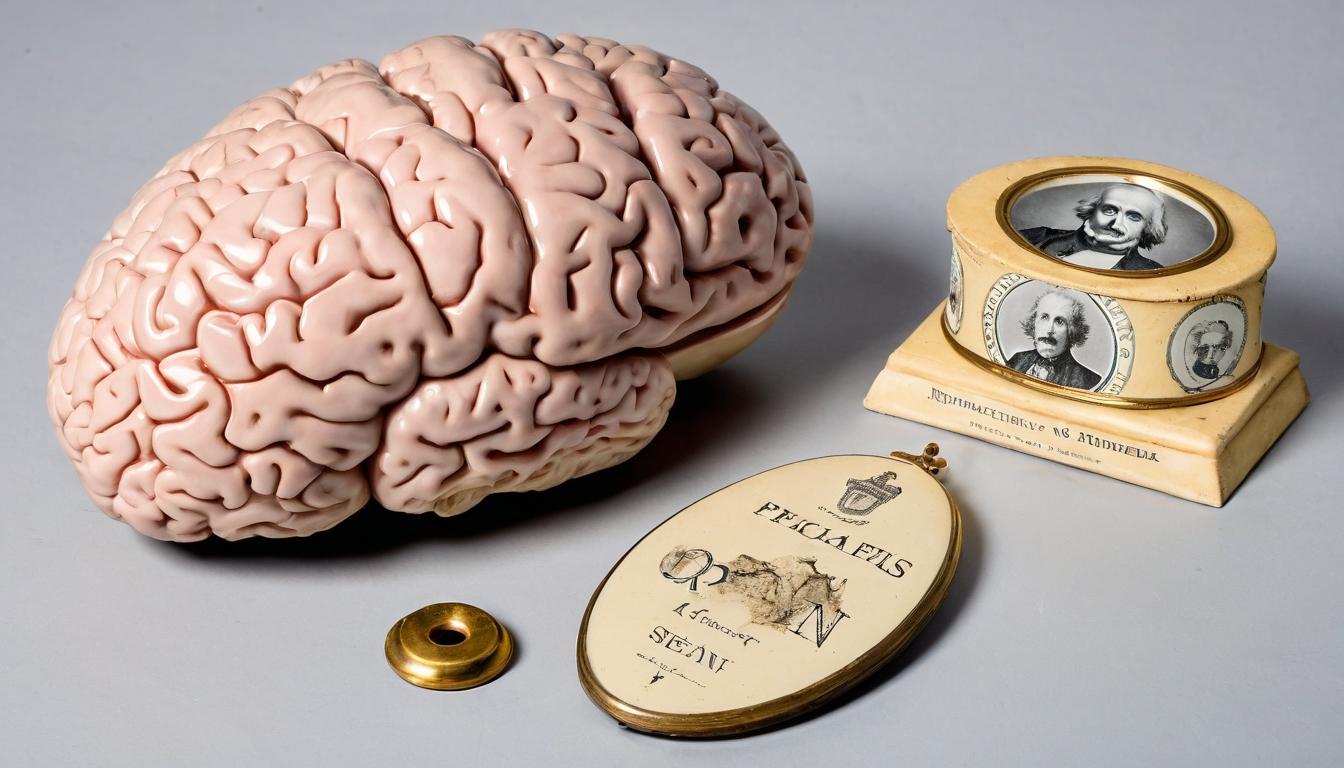

This isn't the only example of bizarre historical collectibles. Abraham Lincoln's skull fragments from his assassination are preserved at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, while pieces of the railroad tie that supported his deathbed were carved into souvenirs and distributed to dignitaries. Even Einstein's brain took a strange postmortem journey—removed during autopsy without permission, it was preserved in jars and studied for decades before being returned to his family.

The phenomenon of relic collecting stretches back centuries, with medieval churches famously claiming possession of countless splinters from the 'true cross' and enough saintly bones to reconstruct multiple skeletons. What drives this fascination with physical remnants of history? Psychologists suggest it represents a tangible connection to the past, a way to touch history literally rather than just read about it. For collectors, these artifacts become conversation pieces that carry stories far beyond their physical form.

Modern technology has created new categories of bizarre collectibles. The first tweet ever sent by Jack Dorsey sold as an NFT for $2.9 million, while a partially eaten grilled cheese sandwich that supposedly bore the image of the Virgin Mary fetched $28,000 on eBay. These items reveal how our definition of historical significance continues to evolve in strange directions.

Perhaps the most curious aspect of these artifact journeys is what they reveal about human nature itself. We seem hardwired to find meaning in objects, to create relics where none naturally exist, and to preserve the physical remnants of those we admire—or even those we oppose. The blackened, twisted remains of the World Trade Center became memorial artifacts, while pieces of the Berlin Wall were chipped away by tourists seeking their own piece of history.

These objects, whether Napoleon's disputed penis or a chunk of concrete from a fallen barrier, become more than their material substance. They transform into symbols, conversation starters, and physical manifestations of historical moments. They remind us that history isn't just dates and documents—it's also the strange, personal, and sometimes uncomfortable physical remnants that survive long after events have faded from memory.

The market for these artifacts continues to thrive, with auction houses regularly offering everything from celebrity hair clippings to historical documents stained with famous blood. Each sale reveals something about our collective fascination with touching the past, however bizarre the method might be. As technology advances, we may see even stranger historical artifacts emerge—perhaps the first AI's source code or the original prototype of the first smartphone.

What remains constant is our human desire to connect with history through physical objects, to hold something that was there when important events unfolded. Whether it's a piece of a famous person's body or a fragment of a historic structure, these artifacts satisfy a deep need for tangible connection to the stories that shape our world. They remind us that history is messy, strange, and often far more interesting than the sanitized versions we encounter in textbooks.

The curious case of Napoleon's stolen penis and other bizarre historical artifacts